The BBC reports this week that, from the beginning of the 2008 / 09 academic year, Britain's involvement in the slave trade is to be studied by all secondary pupils in England.

When I began university, I studied a core module in the first year called "Black Atlantic: Slavery and it's Legacies". The title, you may notice, is related to a book by Paul Gilroy, but that's not the point. I came out of the first lecture scared. I was not scared by the horrors of slavery (I guess the MTV generation has become passive to images and tales of gore and suffering), but what troubled me personally was that I had gone through my entire childhood without realising that Britain -- the country of which I had always considered myself but a loyal servant -- committed one of the most terrible crimes of modern civilisation. I knew of the Holocaust, which accounted for the deaths of millions of people because of their religion, but I knew not of fates worse than death bore out by African people over timescales of centuries instead of decades. I felt ignorant and out of touch with a passage of history so gruesome and wrong that I simply began to crave knowledge and understanding on a phenomenal and bewildering scale.

What hurt the most was the sudden realisation that slavery and the slave trade mattered. They mattered as early as the sixteenth century, and they still matter here in the twenty-first.

I studied my degree at the University of Liverpool John Moores: the streets I walked down to get to class were, and still are, named after the slave traders. Under the picture on the BBC web site, the caption reads: "pupils will be urged to look at the long term impacts of slavery". While this simply has to be the case if the learning is to be worthwhile, it is worth remembering that the legacies of slavery are not purely aesthetic in terms of the microcosm of Liverpool. As often as raindrops fall upon Liverpool the city tries to cleanse itself, yet it longs for a cleanliness which seems to forever be out of reach, as the raindrops come laced with the blood of the slaves. The same is true of Bristol. The same is true of London.

The only time I ever came close to touching upon the slave trade was in the sixth form at school, when I was studying A-level government & politics. We learnt of about thirty Supreme Court cases in a single one hour lesson. Dred Scott vs Sandford, 1857 passed by in a single sentence: "no slave could be a citizen of the United States" said the teacher. "Next one, Plessy vs Ferguson, 1897," he continued, "the legalisation of segregation in America. This was overturned in the 50's with the case Brown vs Board of Education." In about thirty seconds we covered the spine of African-American history with regard to the U.S. Supreme Court. I can't recall them being mentioned again in class, but I still remember thinking at the time: "slaves? Segregation? There's no connection there." Thankfully I did my reading and I did my research. Twelve months later, in my first year at university.

Until now, the neglect of the slave trade and slavery from the curriculum sticks out like a sore thumb. To not teach the slave trade and slavery and the legacies of both is to effectively deny that they happened.

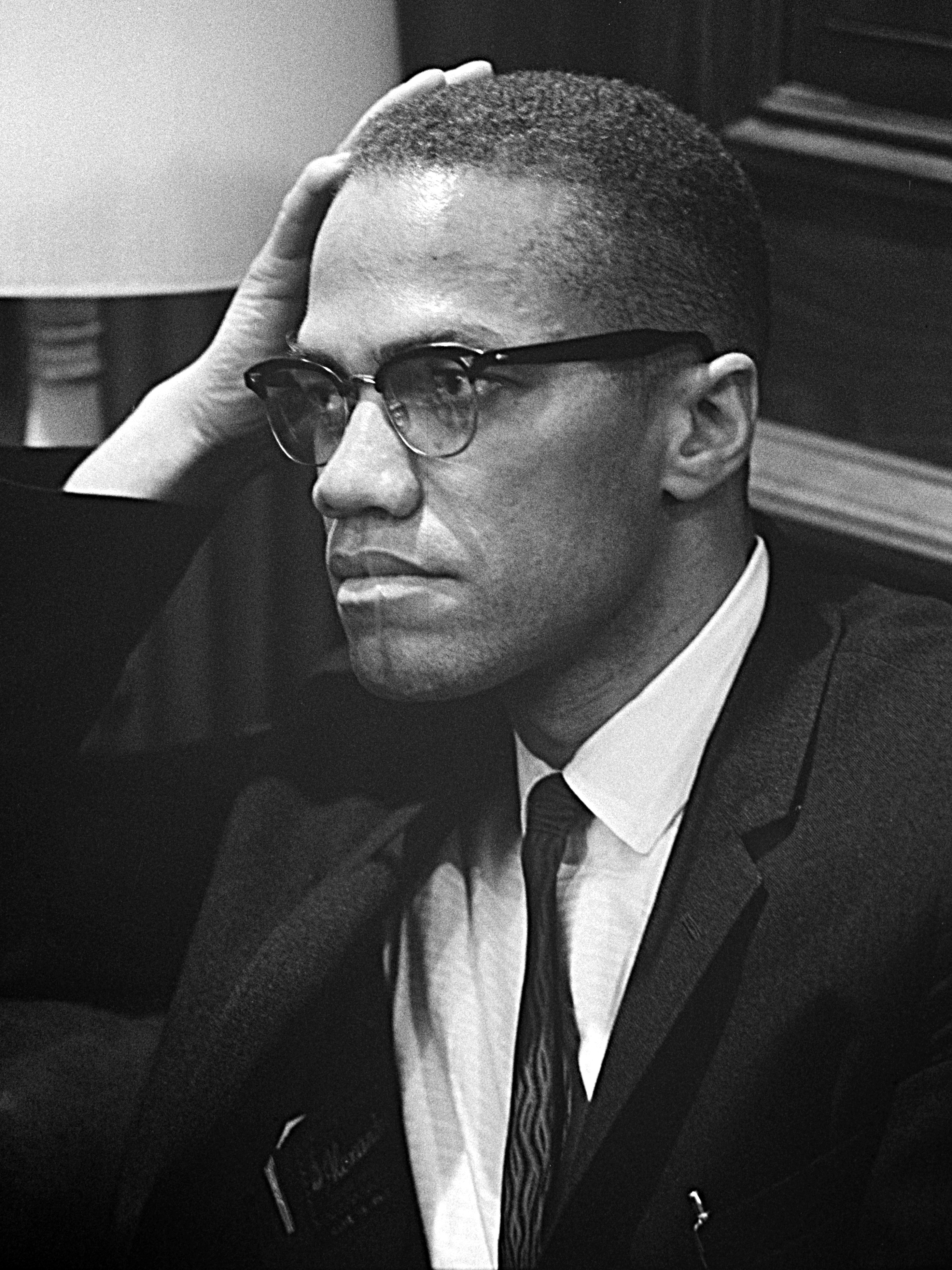

There's currently a 'comment' up on the BBC web site simply saying the teaching of slavery should not be compulsory, made by Vic, UK. Hmmm. Should pupils learn the concept of equality? Are people of African descent equal to people of European descent? Should pupils learn that everyone should be judged by the content of their character and not by the colour of their skin? (I am assuming the answer is an unwavering 'yes', there). By making slavery compulsory it makes the civil rights movement easier to contextualise -- I find it hard to believe I read King's speech and discussed it in class without taking slavery and the slave trade into account whatsoever. The philosophy of Malcolm X is so misunderstood in high school history that schools won't touch it with a barge pole. On face value it's an angry black man shouting "the white man is the devil!" He shouts the white man is the devil because the white man enslaved the black man for three hundred years, and even though Lincoln "freed" the slaves in 1865, African-Americans were still not free when he (Malcolm X) was assassinated and were still second-class citizens then, 100 years after "freedom". Those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it.

The election of Barack Obama to the White House will not put an end to racial prejudice, in the same way that racial prejudice did not begin with the slave trade. But the picture is a complex one: racial prejudice, the political career of Barack Obama, and the slave trade are all carefully interwoven. You can't learn about two of them without the third one. In between these three, of course, there are many more important factors which also cannot be ignored...

Yours, wherever you may be,

Daniel C. Wright

No comments:

Post a Comment